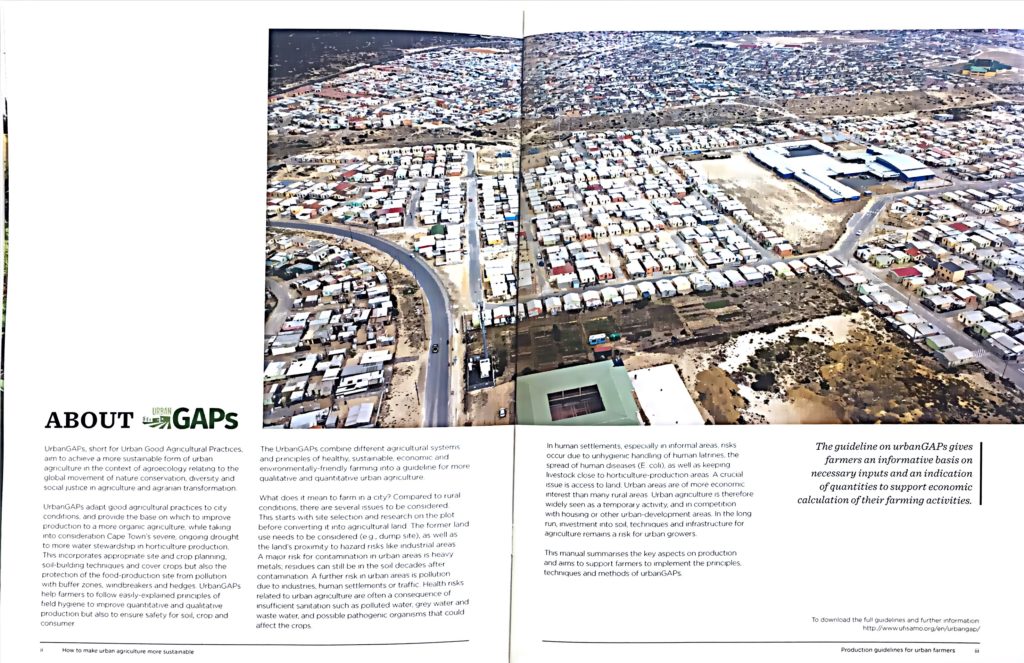

In 2014, Abalimi Bezekhaya put its name in a proposal with Humboldt University in Berlin, Germany for funding from the German Department of Agriculture to create a research project to assess urban agriculture (UA) in both Cape Town, South Africa and Maputo, Moçambique, titled UFISAMO (Urban agriculture for Food security and Income generation in South Africa and MOçambique).

This 3-year partnership running from 2016-2019 would characterize UA in both cities, analyze the gaps in the value chains, and produce outcomes aiming at bridging the gaps. Specifically focused on fresh vegetable production and chicken rearing, one of the major gaps identified in Cape Town was a lack of market options for small-scale farmers, including those of Abalimi Bezekhaya. Harvest of Hope, Abalimi’s market project for the farmers it trained, had created dependency of the farmers on its subsidies and market access. It could have been its mission to be a market incubator which trained farmers to access and create its own markets, but this output, which was internally recognized, wasn’t realized due to a lack of leadership. Instead it became a well-known sales brand which kept the farmers to itself, stagnating growth. It was highly popular for its social aims, but ultimately limited the ~150 farmers it sought to develop.

The UFISAMO research fellows recognized this weakness in the UA value chain and focused its energy on developing materials for farmers to broaden their market access opportunities. “UrbanGAPs for Urban Agriculture, Cape Town Edition for Vegetables” is the ultimate achievement of this partnership. To access markets generally speaking, farmers need to meet certain standards in production and handling of produce. One such standard to be able to sell to supermarkets is “GlobalGAP”. This standard and certification allows farmers to export to other countries. But this requires consultants to be paid to certify your farm annually. These costs are out of the range of earnings for the smallholder farmers of the Cape Flats who have low income and limited financial resources. Even more inaccessible is organic certification like the USDA and EU standards, which allows farmers to sell their products with “Organic” branding. But why should small-holder farmers be kept from achieving the same market opportunities when they are growing produce in a more natural and responsible way than many who can afford the certifications?

UrbanGAPs, along with Participatory Guarantee System (PGS) organic certification, provides the bridge that small-holder farmers have need to sell in the greater marketplace. It is the stepping stone to train farmers on vegetable production standards that are both appropriate and possible to implement given limited agricultural and financial resources.

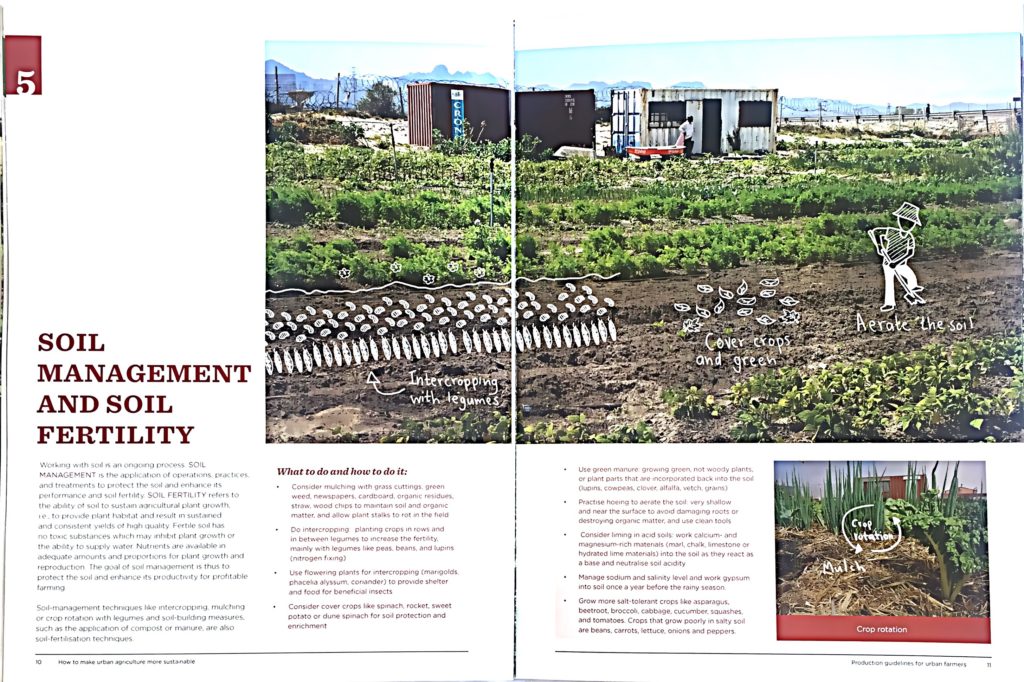

UrbanGAPs address several areas of crop production including farm planning and site selection, crop planning, planting seeds and seedlings, how to prepare land and soil, how to manage soil fertility, fertilizing crops, managing irrigation, managing pests and diseases, field hygiene, and harvesting to post-harvesting.

The standard has entered its testing phase where the Urban Farmers Research Group will evaluate the standards for several months. Their feedback will then be incorporated into the published standard which has been preliminarily accepted by IFOAM, the international organic standards body. I am happy to have been a reviewer for the UrbanGAPs standards and hope to be apart of developing the monitoring standards further.

Find out more about UFISAMO and its outputs on its website here.

Find out more about UrbanGAPs and download the guide here.

Find out more about organic crop standards at IFOAM’s website here.