Ouro Sogui is the largest town in the Matam region of Senegal, but is definitely a small town when it comes to area, population, and businesses. Four banks, three gas stations, one roundabout, no traffic lights. About 10 kms from the Senegal River—the border to Mauritania—this is considered an important commercial link. The tallest buildings around town are the minarets of the dozen mosques around town. Senegal is 95% Muslim, with a proud tradition of tolerance to all beliefs.

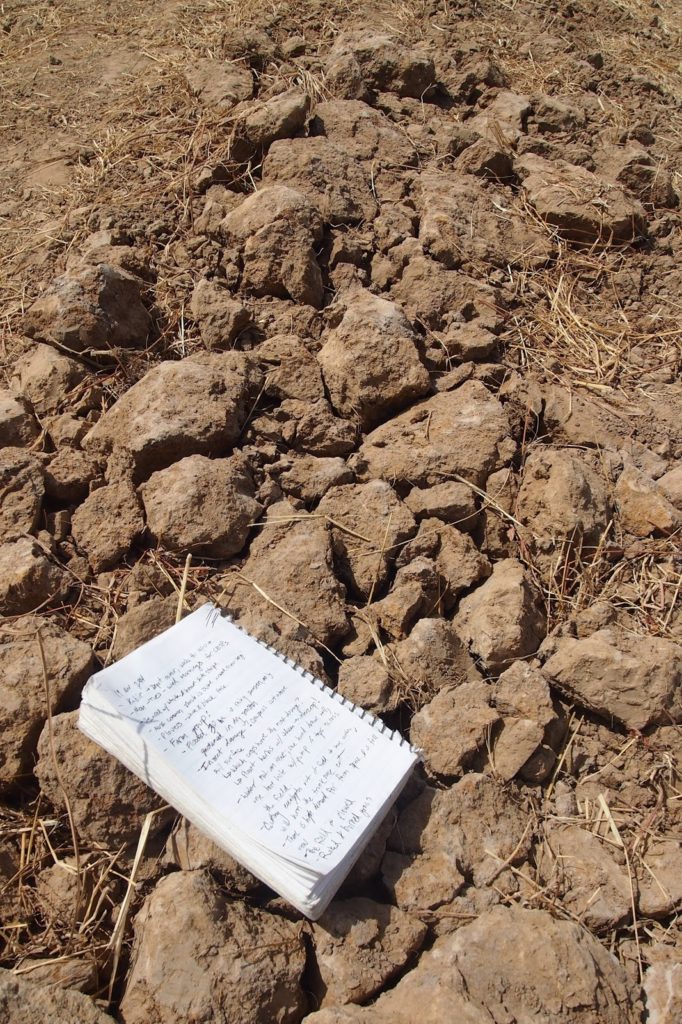

On the eastern outskirts of town the soil is mostly clay and a seasonal flood plain that runs off directly to the river. Looking at the soil verifies what the farmers know. There are signs of redox: a reduced iron matrix and oxidized iron mottling, and this is the top horizon in the garden area; directly mineral and indurrated. Due to overgrazing in the entire region, there isn’t likely to be any difference going to look for an ideal, virgin soil. Erosion is everywhere, and top soil would be hard to find near any road or path. There is no organic matter.

As soon as one begins to dig in the soil one discovers that is is rock hard. As you slowly succeed in breaking it apart, it appears to come apart in huge rocks. Don’t ask for a shovel because what you will be handed is the thinest, flimsiest piece of ‘metal’ you’ve ever seen that would break if you pushed too hard. When the farmers are ready to plant they water the soil first so it is easier to work, and then jump in with a pick-ax. Water too much though and you will slip and slide on the clay.

The grain crops are mostly planted in the rainy season July to October. Growing millet and sorghum, the farmers are resilient to changes in rainfall (whether very late, long dry periods, or low total amount) since these grains are drought-tolerant species native to Africa. Peanuts are grown in rotation, and sorrel is grown at the end of the rainy season. The planting and harvesting is traditionally performed by the men using animal-pulled plows. Just driving along the road you could see here and there the farmer’s yields of millet stacked over a meter high between poles, like a wood pile between pines.

Most of the year however is dry. In this season, women garden for vegetables, and depending on water availability, grow irrigated maize. They grow lettuce, okra, eggplant, african eggplant (Solanum aethiopicum, pictured right), peppers (sweet and hot), cowpeas, potatoes, carrots, cabbage, tomatoes, with a bit of cassava, mint, and sweet potatoes. The women’s group I trained here extends to gardens around the area, and each woman has a small garden at home.

As a rule, the soil surface is kept clear of plant matter. If there is much grass they will burn it away. This is done after plowing the field after the rains end when it’s no longer flooded. Holes are also utilized for concentrated water use. Within these holes (which some were calling Zai though there are no mounds) a pole is used to create a 5 cm deep plug into which the seeds are dropped. It seems to give the seedlings deeper rooting depth and better access to moisture as water is funneled to it.

This climate is on the brink of arid with a purported rainfall around 400mm a year, with maximums near 600mm (the average at Ukulima). Florida gets this much rain in just two summer months. Because of this water resources have been well developed. The ground water here is plentiful and this garden has a new pump for a deep borehole. Taps throughout the garden allow the gardeners to water more conveniently, though one can only water every other day in the morning. By noon the pump is turned off to conserve fuel. To be able to water later in the day many have repurposed oil drums to hold water. They fill it up when the pump is on and then can water later in the day or at night if transplanting.

On site there is also an open well. When the pump is off there is the option of drawing water from the well, one small bucket at a time. One of the farmers insisted I try pulling one up. Having never done it before I was excited to try. Letting the plastic bucket drop to the bottom and fill, it wasn’t too difficult to pull up quickly, but I didn’t have to water large plots and pull up full buckets all day to do it. Once they apply the water onto the soil it typically ponds as the clay expands. In adaptation to this they use a system of trenching and sunken beds that enable them to flood the bed and let the water slowly infiltrate without running off. If manure and urea are applied, they are broadcast over the bed and left on the surface.

After our tour of the garden, Abibou and I sat down in his office to check email and do some research. I told him how interesting it was too see what the farmers were already doing. Half of what they did seemed to be adapted to their environment and circumstances, and that the other half was habit, doing what they’ve always done and seen others do. Immediately Abibou says, “80. 80 or 90.” I look at him for a second, confused. I started laughing as soon as I understood. He laughed with me. He thought as much as 90% of what these farmers were doing was just habit. No other reason. “It’s the same in the US,” I responded. It is always surprising when you see a new facet to how universal human nature really is.